Last week the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre laid off most of its sales and marketing staff, while encouraging its unpaid performers and writers, whom it stressed it has no intentions to pay, to put more effort into promoting their shows.

Faced with rising rent and property taxes, the company let go eight employees, including the East Village theatre’s house manager and a training center administrator. In a series of emails and in-person meetings with staff and performers, UCB’s leadership described these moves as a matter of life and death for the company, which has been operating at a deficit for at least two years. On Wednesday they announced the hiring of a chief financial officer, to start in January, and the formation of a “performer advocate group” to serve as a liaison between the theatre’s community and its management. They did not specify how this body would function or on what specific issues. When asked if it would have a say in major organizational decisions, UCB founder Ian Roberts struggled to understand the question.

Responding to concerns about the potential closure of UCB East, founders Matt Besser, Roberts and Amy Poehler said there are no immediate plans to do so. They cautioned that its future is not certain, however, due to dramatic increases in property taxes. (About $30,000 over the last two years on top of a preexisting $68,000, according to a source with direct knowledge.) If negotiations with the Beast’s landlord yield no solution, they said, it would not close without an alternative venue for its programming; the Hell’s Kitchen space is locked into a 15-year lease and not going anywhere soon. In the meantime, New York artistic director Michael Hartney predicted that the price of admission to weekend shows might increase, while stressing that training center tuition will not. A previously announced plan to pay house team coaches, currently paid by talent, was indefinitely postponed.

Despite these measures, it is clear that UCB’s owners have no cogent vision for the theatre’s future. Or rather, they have one very limited vision: getting out of the red. One source present at a December 11th staff meeting described a human resources manager asking Besser if the company had a 30-60-90 day plan; he did not know. Poehler and Roberts were asked about their long-term goals at an all-theatre meeting on the 17th and responded in kind. Roberts said he doesn’t have any benchmarks other than not running at a deficit six months from now, as he cannot financially support the company beyond that. Poehler said her goal is to ensure the theaters and schools are “really robust” and that “business is booming,” per a recording of that meeting. “There’s no two-year plan,” she said.

Interviews with eleven members of the UCB community—including current and former employees—as well as leaked audio of the December 17th meeting describe a company in financial and organizational crisis. In both meetings with staff and talent, Besser, Poehler and Roberts plainly stated that they never wanted to run a theatre; they wanted to be comedians. So they allowed each coast’s operation to run autonomously while they kept their hands off the wheel. Still, Michael Hartney—new to the job but already widely beloved—told performers in a December 12th all-theatre meeting that he does not have complete access to his theaters’ financial information. Shannon O’Neill, his predecessor, said the same was true during her tenure. Hartney noted that the New York theaters were consistently beating attendance benchmarks provided by management, suggesting management had inaccurate metrics for success. Multiple sources said Hartney seemed as frustrated and in the dark as them: he had no answers to questions about who ordered the layoffs, for instance, or who would pick up the slack for departing employees.

At the same time, UCB’s owners insisted at both the December 11th and 17th meetings that they had no idea UCB was in financial trouble until very recently. On the 11th, Besser told staff that UCB’s development deal with Seeso had “masked two years of deficits,” according to meeting minutes I’ve obtained, and that he and Poehler had not even been aware of two payroll delays in November. (A third delay, on December 14th, was later attributed to the layoff of the employee handling payroll.) On the 17th, Roberts said UCB’s June promise to pay coaches had been made with an incomplete understanding of the company’s finances. “We've gotten information since then that we're doing far worse than we thought,” he said. Alex Sidtis, UCB’s New York managing director, who recently moved to California, apologized at that meeting for falling short of his and the community’s expectations. Nonetheless, it remains unclear what accounts for the magnitude of these disconnects, who exactly has been responsible for UCB’s financial well-being, and why they failed.

“The bottom line is they’ve treated performers as not being stakeholders,” one UCB performer told me last week. It’s a sentiment that’s been bubbling throughout the community for some time. Last year UCB shuttered its Chelsea theatre and relocated to Hell’s Kitchen, a move designed to solve a longstanding ADA-noncompliance issue. Several long blocks west of Times Square, the new space has suffered poor attendance—Hartney confirmed on the 12th that it has seen lower sales compared to Chelsea—and the loss of at least one tentpole, the alternative standup showcase Whiplash. There is also widespread concern among performers and writers that industry representatives—managers, agents, casting directors—are not coming out to Hell’s Kitchen as often as they came to Chelsea, depriving talent of one of the few pipelines to monetary compensation that UCB offers. A list of community questions for leadership that circulated last week includes several about the move, revealing the extent to which it is considered a self-evidently bad call:

How long is our Hell's Kitchen lease for and do we envision remaining at the space even if the financial implications of doing so may lead to further layoffs, UCB East shuttering, etc?

There’s more or less a consensus amongst performers that the HK acquisition was a poor fit for our community. What actions are being taken to make sure future major decisions have the community’s opinions and needs in mind?

Can you tell us more of the backstory of how and why the move to HK was originally made? FOLLOW UP: Can you describe in general how theatre-level decisions are made?

If you had asked performers who live and work in the city on their thoughts regarding a move to Hell’s Kitchen, you would’ve received overwhelming feedback that the move is ill-advised. Plenty of us with day jobs have non-comedy coworkers who used to regularly attend shows at Chelsea but will never go to Hell’s Kitchen because of its inconvenient location. Moving forward, how will the UCB incorporate the community in its decision making?

At the all-theatre meeting on the 17th, Roberts explained that the move was intended to do more than make the theatre more accessible. UCB was anticipating a debilitating rent hike in Chelsea, where it had a very short lease; the 15-year lease at Hell’s Kitchen would save money in the long run. They didn’t consult the community, Sidtis added, because they were bidding on the space at auction and felt that going public prematurely would put them at a disadvantage. “It takes huge lead time to find a theater,” Roberts said. “Theaters are like unicorns. To find a place that can take a theater—this had a certificate of occupancy, we could grab it and we could guarantee that you guys have a home. This is a positive. We have a 15-year lease here. It's not going anywhere. You guys are gonna have a place to perform.”

This answer is revealing in that it suggests the UCB 4 took as a foregone conclusion that acquiring a new space was the right decision; the only questions were where and how much. They apparently did not consider whether a more prudent response to the spiraling costs of operating two theaters in Manhattan might be to not operate two theaters in Manhattan. This would have been a drastic decision, but it is also roughly the decision UCB faces now, a year later and with eight fewer employees. More importantly, it is exactly the sort of decision that would have benefited from the input of those who perform the bulk of UCB’s labor. A listening period before the fact might have identified other priorities beyond simply having a place to perform, e.g. a business model that is sustainable in the long-term, compensation for labor, or even just some evidence that audiences and industry would come to that place in the same numbers.

A small level of outreach would have done more than help UCB make an informed call: it would have built needed trust and confidence in a community that often feels subjected to the whims of an opaque leadership apparatus 3,000 miles away. That UCB skipped this step in such a consequential decision suggests it did not truly understand those consequences, at least for the workers who have to live with them. This all takes on an additionally disturbing valence in light of what we know now: that the UCB 4 approved the Hell’s Kitchen move unaware UCB was in financial jeopardy, a fact that somehow did not emerge during the process of bidding on and leasing a new theatre.

This is what’s so baffling about the UCB 4. Time and again they’ve declared they take no paycheck from UCB. Now they reveal they’ve been absentee owners with no interest in running a theatre company. Still they maintain strict control over corporate decision-making—Roberts said on the 17th that no major decision gets made without crossing his desk—and refuse to cede any power or transparency to their workforce. They don’t want the job, they don’t profit from the job, they haven’t been doing the job, and they’re not good at the job. So why do they still have the job?

What’s emerged over the last two weeks is a picture of four very successful comedians—well, three; Matt Walsh is committing to the absentee bit—who feel they have done a huge favor for a group of young people who don’t appreciate how good they have it. One of the two big announcements Poehler and Roberts made on the 17th was the creation of a “performer advocate group.” (The other was the hiring of an unnamed CFO with experience rescuing an unspecified artistic organization from crisis.) They had no plans for what this group what look like or how it would function. Hartney said the community would shape it, and perhaps it would convey concerns to upper management in a quarterly call. “We just want to make sure that stuff isn't festering in this community,” he said, “and that we can be on top of it when it requires bigger steps of action taken by upper management and ownership.”

Roberts, however, soon made clear how little he understands issues that have been festering for years. During a Q+A session, someone asked if the group will have a role in UCB’s leadership. “I think it's an amazing idea and I'm very thankful,” she said. "I do want to make sure it's not one-sided and us bringing our issues, but that we have a seat at the table before any major decisions are being made.”

“I’m not quite following,” Roberts responded. He asked for an example; she offered the possibility that a theatre has to close. Would they inform the group before they make the call?

“I just want to clarify,” he said. “So for instance, I told you that we’re working on both negotiating and finding another option” for UCB East. “So if I told you that, is that enough? Or at what point before—because we will have gotten all this info and done all this work.”

He asked if she wanted to be involved in the research process or just to get a heads up when a big announcement is coming. “Ideally, best case scenario, we get someone in the room with you,” she said. “But you guys own this theatre, so it's privately owned and as performers we don't necessarily have that much clout, I guess. But that would be nice.”

“Here's one thing that I just want to say,” Roberts said after some back and forth. “I feel with the business—we would love to have everything be an ideal situation. The absolute bottom line has to be that there is a situation. So if the feedback was… ‘I don't like this place as much as Chelsea.’ Okay, but I think what you want before you have your ideal space is that you have a space. So I just want to make that clear. Because I don't want to say, to offer up, ‘tell us how you feel.’ You gotta understand too—sometimes I'm probably going to leave to the CFO how to survive.”

Again the answer assumes what Roberts’ large, varied workforce wants without bothering to ask. It also starts from the paternalistic premise that UCB performers don’t understand the idea of compromise—that a seat at the table won’t guarantee they always get what they want—and further that the seat has no value to them if they don’t. It’s weird, again, because he’s claiming to know better in the same meeting he admitted he doesn’t really know anything. Elsewhere he said he was struck to learn “revenue” is a meaningless metric, because as a business grows so do its costs; elsewhere, that he always thought layoffs meant a company was selfishly trying to hoard profits, but now he knows they might just mean it’s struggling to survive. The guy has nothing but evidence he should stop talking and start listening. I suspect one reason he hasn’t is that he can’t envision his workers saying anything other than that they’re unhappy with him.

What stands out most to me is Roberts’ line that there has to be a situation before there can be an ideal situation. He repeated this several times on the 17th. It’s a true enough platitude and a nice way of telling people to be grateful for what they have. The problem is that at no point in the last two weeks—or ever, to my knowledge—have the UCB 4 articulated what an “ideal situation” might be. There’s no two-year plan; there’s only getting rid of the deficit. At this point I think it’s safe to say they just haven’t bothered to think about what UCB could become and how they’d get there, or more generously that they’ve delegated the job to each theatre’s artistic staff. Still it remains hugely disappointing that four talented comedians have declined to use their imaginative powers to envision, say, a world where each theatre is profitable, sustainable, and able to pay its performers. If they truly don’t want to do that themselves, they have a vast community happy to do it for them. In the absence of that vision—if the “situation” is not actually a step toward an “ideal situation”—Roberts’ mantra is meaningless. He’s just telling people not to complain.

It seems to me the UCB 4 don’t think of themselves as leaders of an artistic organization but as providers of an artistic service. At the December 11th staff meeting, according to two people there, Matt Besser reiterated the philosophy about pay he has stated many times before: UCB gives writers and performers a platform where they can get good at comedy; when they get good, they can go elsewhere and get paid; UCB isn’t trying to make a profit, it’s trying to make comedians. The most important thing to know about this is that whether or not you are making a profit has no bearing on whether you must pay your workers. “The last time I checked, UCB was incorporated as a for-profit corporation,” Chicago-based labor attorney Will Bloom told me. “But even if UCB was a not-for-profit, that would not change their legal obligation to the people doing the work at the center of UCB's mission. The ACLU is just as bound by minimum wage laws as Amazon. The same goes for UCB.”

The second most important thing to know about UCB’s pay philosophy is that it represents an utterly toxic relationship between theatre and talent. What it says to the people who have found a home at UCB is that if they ever want to be compensated for their labor then they must leave the place they love. What it says to the people searching for a home at UCB is that they can only do what they love if they are willing to lose money doing it. I find it endlessly depressing that UCB has coerced entire generations of comedians into accepting this. As I have written elsewhere, UCB’s refusal to pay its workers has devastating effects on diversity at the theatre and in the industry more broadly, not to mention the likelihood that it’s totally illegal. But at heart it’s just a tragedy. I wouldn’t even know how to start quantifying the number of people who have been kept out of comedy by the system UCB established.

The problem, in other words, is that UCB’s owners view their employees as their customers. As such they feel no obligation to compensate the people they think they are working for, nor any obligation to involve them in that work. It would be like a restaurant allowing its patrons to decide the menu. (No matter that in UCB’s case the patrons are also the cooks). The extent of the obligation they do feel is to listen to their customers’ concerns—as Poehler told Roberts many times on the 17th, “They just want to be heard”—and then apply their own unilateral judgment accordingly.

Many in the community, of course, want much more than to be heard.

Here’s what Poehler and Roberts had to say about pay.

About 45 minutes into the meeting, someone asked if upper management can be more transparent. “It's so hard to know what's going on without better financial or corporate transparency,” she said. “If there is eventually a talent liaison or something, is that information that can be shared with them? Especially corporate structure… There are these things like the show at Carnegie Hall, or like when ASSSSCAT goes to SF Sketchfest or South by Southwest—where does that money come from to send them there? Where does the profit go from those shows? Where do book sales go? Any of that stuff—who is whose boss?”

“We hear you,” Poehler replied. “I think that's something we should talk about and make—let's think about that, how that would work, where people feel like they're more informed and more clear.”

Then someone interjected to defend UCB’s right to privacy. “I own a production company. If somebody asked me what my finances were, I'd be super offended,” she said. “I understand wanting to know more information, but at the same time this theatre is still a business, it’s still their theatre.”

Karen Anglade, UCB’s New York HR manager, agreed. “This is a privately owned company,” she said. “They’re not subject to the same disclosures necessarily as a major corporation.” Anglade had pointed out earlier that most companies don’t hold meetings to address layoffs. “I think it's just really cool that they're here and they're being as transparent as possible,” she said then. “Asking for specific numbers actually won't do anybody any good, because in the total picture you probably wouldn't see why what had to be done.”

At this point another performer interrupted with a heated critique of UCB’s business model and strategy. He has been identified to me as Nat Towsen, a standup comic who hosts a monthly variety show at UCB East and runs the New York arm of UCB Corps, the theatre’s volunteer program. (Towsen confirmed he made the speech, but declined to say any more on record.) I think what he said is worth reading in full, as is Roberts’ response. Both are transcribed below, with occasional jumps where I can’t quite make out the audio.

Everyone in this room works for this theatre. But most of us are not paid. So it's very frustrating to hear how lucky we are to receive future transparency and communication that will apparently someday exist when we're being asked to work for free no matter what, all the time. And you said we're very lucky. Why—“it’s not a corporation… Why would we disclose something?” Well, because everybody in this room could just suddenly stop working and lose nothing. We would lose no financial stability from that. I don't want to do that, we all love being here… You say the growth was mismanaged, right? I've been at this theater for a while. Five years ago, there was a huge controversy, the New York Times wrote an article about it. You stood onstage and you said, "Trust us." Not only that, you said, "Stick up for us next time. Next time people say you should be paid, tell them why you shouldn't be paid." And we all trusted you. And then you took the money that you make from our labor—and by the way, it's not just ticket sales, it's the fact that we are all a living advertisement for your school—and you took that money and you expanded too quickly. Now you're in financial trouble. You open two theaters, two training centers and the fifth theater—which is ucbcomedy.com, which as far as I can tell makes no money—and you use all of our labor to pay for all that stuff. And now we find out that we're operating at a deficit.

What it feels like to me is that instead of rapid growth, you could have found a sustainable model for a theater that you pay people a little bit. The problem we have right now is that agents and opportunities aren't coming here as much as they used to be. You have a self-selection problem. Besser stood onstage and said, "Hey, when you're good, you can go somewhere else." Guess what—people took that to heart and they left the theater. There's a reason a lot of talented people are over at Union Hall or Caveat or other venues where now agents are going and looking for people. So if we're being paid in stage time and opportunity, and now the opportunities aren't there, you're also cutting that form of pay. So it feels to me as if that growth was not only reckless, but you also violated our trust. Everyone in this room looks up to you and I think—I want to hear more than how you're going to openly communicate with us in the future. I want to hear how you're going to find a sustainable model that can support your performers.

The speech was followed by a burst of applause, then some crosstalk before Roberts responded substantively. First he asked if he was right to assume that those who clapped agreed with the central points about pay; then another performer spoke up to say that it’s not about pay, it’s about opportunity, which is drying up with diminishing industry attendance; Hartney emphatically denied this is actually happening; and Roberts agreed:

I think that’s completely false, personally. I work in this industry and I have people tell me how amazing the UCB is… So I don't think that’s true. But the part I can respond to is pay. And I'll continue to respond to that. I believe the growth of this theatre helped you. I don't know what you imagine it's doing for me, but it gave you—we opened stages so more people have opportunity. So I don't understand what you think my endgame is. If I opened other theaters and you're mad at me, I acknowledge that I made mistakes, I mean, because I have to. It's like an "ergo" situation: If a place has found itself in financial trouble, something must have been done wrong. How else could it get there? I don't believe what was done wrong is opening second theaters and giving fully twice as many people opportunities to perform. And as far as people not getting paid. Here's the situation that existed before we had this theatre. You went and you rented space to put up your show. I don't think—I just think it's reciprocal is all. I'm giving you a place where normally you'd have to rent it. What's a night cost for us to be open? You owe me a third of that, if you want to be paid, and then we can give you the door. Pay me the utilities, pay me the employees, pay me the percentage of the rent and we can do that.

Pay us and then we’ll pay you.

The UCB 4 don’t get it. Well, Amy Poehler might get it, but if she does I don’t think she’s going to do anything about it. She spent a good deal of the December 17th meeting in PR mode, cutting off Roberts when he started digging himself into a hole, telling talent she heard them and would continue listening; she spent very little addressing the substance of their concerns. (In response to the pay discussion she resignedly told Roberts, “I don’t want to get into the morass about paying.”) It’s possible she’ll engage more meaningfully with the performer advocate group once it gets off the ground, but no one I have spoken to expects that group will be given any real power. Either way, the UCB community made clear and consistent asks for transparency, accountability, and strategy. Poehler and Roberts had many explicit opportunities to provide or at least promise those things. They did not. In multiple instances they balked at the very idea. I would be deeply surprised if their new chief financial officer is any more receptive to the community’s demands.

There are several issues coalescing here. One is that the UCB 4, for unclear reasons, refuse to cede the power they don’t want or know what to do with. (UCB did not respond to multiple requests for comment.) Another is the failure of communication between the UCB 4 and their subordinate managers, and by extension between the UCB 4 and UCB’s workforce. A third is that the UCB 4 just don’t know what it’s like to be an emerging comedian in 2018. Poehler told Towsen she understands where he’s coming from; they all used to be young comedians too, after all. But the fact that they stand by their pay model shows they don’t actually grasp how times have changed since they came up. Costs of living have risen; wages have stagnated; the barriers to entry are all but insurmountable. What’s more shocking is that they don’t even seem to understand what it’s like to be a comedian at UCB. In his argument that performers should pay UCB if they want to get paid in return, Roberts somehow overlooked that UCB charges its performers thousands of dollars before they reach the stage. Later he reacted with disbelief as performers called out the additional expenses they have to shoulder once they get there: coaches, props, promotion. These are all simple facts of life for anyone who has stepped on a UCB stage. They were news to Roberts.

All of these issues boil down to one root problem: UCB’s owners do not recognize their employees as employees. Until this changes it is difficult to expect they will meaningfully address those employees’ concerns. Until they meaningfully address their employees’ concerns it is impossible to imagine the situation reaching anything close to stability, at least in a sense that extends beyond the UCB 4.

The community has asked nicely. It will soon find out whether asking nicely is enough.

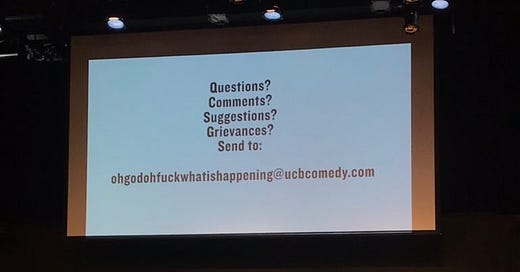

Hello! Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this, please consider sharing it. This newsletter is free for the time being, but any support you can offer will go toward more like it. Comments, tips, corrections, and other stray thoughts are always welcome here or on Twitter, where my DMs are open. Bye bye.